Women/Pioneers, directed by Michal Aviad. Israel, 2013.

“When we got here, we met the women who preceded us. When we saw their suntanned faces, we each asked ourselves: Will you give your face, your body, to this desolate land?”

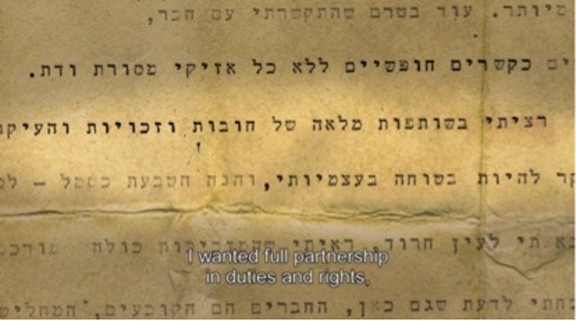

A hundred years ago, women emigrated from Europe to Palestine to establish the kibbutz of Ein Harod. Their diaries and letters are filled with questions, concerns, and a dream to create a new, independent woman. One writer laments that her hands are too small to carry bushels of hay. Another woman is struck with terror at the prospect of crossing paths with an Arab. A third diarist questions whether she should wear her mother’s wedding ring on the kibbutz. The camera pans to her notebook—yellowed pages with scrawls of Hebrew cursive. She writes: “Even before I had a boyfriend, I saw the relationship between two people as a free one, without the shackles of tradition and religion….And this ring is a symbol. Of what?”

Michal Aviad’s film Women/Pioneers, which premiered at this year’s New York Jewish Film Festival, brings these stories to life. Aviad weaves the women’s words (read aloud by narrators) with found archival footage, photographs, and images of the writings. The film offers us a rare glimpse into the lives of five of these women, and with it, a portrait of the tensions and hardships present in the Yishuv, the Jewish settlement communities in Palestine prior to the establishment of the state of Israel.

Like most footage distributed at the time, the Jewish settlers in Women/Pioneers are depicted as productive and strong, taming the wasteland into a fertile abundance of life and creativity. During this era (1920-1948), the Jewish National Fund and the Jewish Agency were commissioning film production aimed primarily to recruit European pioneers from the Jewish Diaspora. These early films, whether documentaries or narrative fictions, reflect the Zionist point of view. Women/Pioneers is similarly composed of black and white footage of settlers paving roads, working the land, and “making the desert bloom.” These images represent (and thus create) the “sabra”—the new Jewish body and psyche that became the antithesis of the weak, degenerate Diaspora Jew. The men in particular are featured as healthy, tanned, and with European features. The construction of the “New Jew” is complete with the successful revival of the Hebrew language. The women featured in the film, including many for whom Hebrew is a second or even third language, choose to use Hebrew to express their most imitate feelings.

The archival footage is also typical in its treatment of the Palestinian Arab majority population. For those behind the camera, whether Zionist filmmakers or European tourists, the Arab represents nothing more than another flower or tree in a barren landscape. The women occasionally write about the indigenous population with the same fear and uncertainty they use to describe their first contact with the land. Upon first encountering the neighboring Palestinian Arab village of Qumia, one of the women writes with pity at the sight of a child covered in mud. She attributes his shoddy appearance to the dirty, tadpole-infested water that the Arab women must fetch. This sentiment is followed with footage of Jewish settlers digging up clean water using the most sophisticated technology. The clear division that the women draw between the negligent lifestyle of the Palestinian Arab peasant and the conscientious vision of the Jewish pioneer is typical of settler colonial discourse. The enterprise of the kibbutz—which celebrated self-sufficiently through exclusively Hebrew labor—reinforced discrimination against Palestinian Arabs and produced new arenas of conflict.

Ultimately, the film challenges and takes apart the egalitarian utopian ideal of the Yishuv. Whereas early Zionist films dared not show any negative aspects of the settlement project for fear of public reprisal and even censorship, Women/Pioneers sheds light on the power dynamics and turmoil that shook early kibbutz life. Departing from visual footage that reflects collective enthusiasm of a national renaissance, the women’s writings reveal the deep hypocrisy at the center of the kibbutz enterprise. They describe their frustration at the non-recognition of their labor as mothers and caregivers, and the challenge of raising children in a collective environment. One woman fights for “motherhood” to become an official category of work on the kibbutz roster. The tension between feminist and socialist goals was not unique to this context. In socialist societies worldwide, feminism was often lost within struggles based on egalitarianism.

The women also struggle with the implications and disillusions of “free love.” In the discussion after the screening at the New York Jewish Film Festival, Aviad explained that three out of the five women had children with men who were powerful leaders of the Zionist movement at the time. These men eventually went on to have children with younger women. The women pioneers in the film express heartbreak more than once, and struggle to consolidate the ideology of an open collective with the sense of betrayal they experience in their individual lives. They also lament their lack of political power within the kibbutz. The managing committee was made up entirely of men, explains one diarist, and the few women who did attend rarely participated. “Is it because they have nothing to say?” she asks rhetorically. These women arrived in Palestine on the backs of three movements: Zionism, socialism, and feminism. It becomes clear that the men only arrived with two.

[Screenshot from Michal Aviad’s Women/Pioneers]

The end of the film hastily covers the Arab revolt of 1936 and the 1948 Arab-Israeli war. The 1936-39 Arab revolt against British colonial rule and Zionist immigration remains a symbol of national unity within Palestinian Arab memory. However, the women’s diaries give no context to the Palestinian struggle, and their “enemy” remains anonymous. Ella Shohat has explained the invisibility of Palestinians in early Zionist films as a deliberate project to subsequently deny them a “solidified national identity.”[1] In the film, the revolt is depicted merely by footage of Jewish men firing into the distance. The women express a desire to participate in warfare, and are frustrated when they are forced to remain in the safe houses with the children while the men conduct battle. In 1948, they gain the “right” to guard the kibbutz with hunting rifles. The film concludes with photographs of these women wielding their guns, implying that they gave up their own liberation for the sake of the national struggle and the settler colonial project.

Their private battle for recognition and equality with their male counterparts fades into history as well. Aviad described the exhausting challenge of finding footage that featured women at all. Camera technology was not well suited to film indoors, where most of women’s work took place. Further, Zionist propaganda footage has always been preoccupied with professional, communal life, which largely excluded women. Pre-state Zionist cinema, as an expression of the settler colonial project, was centered on masculinist hierarchies of thought. The collective experience reigned above that of the individual, the national over the familial, and the public over the private. The Yishuv collective, characterized by an odd blend of socialism and ethnocentrism, left little space for women’s private concerns surrounding love, labor, and decision-making. If Zionist filmography articulates a culture in constant formation, Women/Pioneers adds to the conversation by giving voice to those who were previously absent and by challenging the myth of egalitarian mystique at the heart of the Zionist project.

NOTES

[1] Ella Shohat, Israeli Cinema: East/West and the Politics of Representation (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1989), 55.

![[Screenshot from Michal Aviad’s \"Women/Pioneers\"]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/pioneers1.jpg)